In particular, when a new spec is being developed, during beta it may change. (During a beta of a future version, old specs won’t change.)

So…please do not release non-beta aircraft and scenery based on beta builds like 930.

Here’s an example: the current spec for attached objects is that the draw order is based first on lighting mode, then on the order listed in Plane-Maker.

It turns out that if we do that, polygon offset can’t be used in a number of weird cases. So the rules will have to change. I’m not sure what they will change to, but the decision will be finalized when 930 is finalized.

I receive a number of requests from authors for an attribute to tag an object as “needs maximum texture resolution” or “needs compression disabled” or “needs maximum anisotropic filtering”. The general idea is that the author wants to ensure a viewing environment that looks good.

For the most part, I am against these ideas – think of the two cases:

- If the attribute on the content is request for a relative improvement in resolution (e.g. set my object to one texture res higher than the rest of the world) then what we’ll have is an arms race – every author will set their content with this flag, and the result will be that the entire sim tends to run at one res setting higher than expected. The result: users without enough VRAM will turn their res settings down another notch and all the content will look like it did before.

- If the attribute on the content is a request for an absolute setting (e.g. load this texture at the highest resolution possible) some content will simply not run on some computers that do run X-Plane.

My general point is this: users run X-Plane with texture resolution, anisotropic filtering, and compression set to lower settings for a reason – because their hardware isn’t very fast! Forcing the sim to ignore the settings and run at a higher res won’t make the user’s video card any better – it will just take the framerate vs. visual quality tradeoff out of the hands of the user.

That’s a simplification of the issue – in fact I am sympathetic to the notion of differential settings – that is, we need to use more texture resolution for art elements that are closer to the viewer. The sim already improves airplane resolution a bit and cockpit resolution a lot. We set anisotropic filtering a bit higher on runways because they are viewed from a shallow view angle pretty much all the time during normal flight.

At this point I am looking at some more specific overrides for cockpit objects. In particular, modern cockpits are built out of many attached objects, and not just the “cockpit object” itself – reducing the resolution of these objects can make cockpit labels illegible.

If we do get extensions to improve resolution I can only say this: use them very, very sparingly! Adding the extension doesn’t improve the user’s hardware. If the user had the ability to run your airplane at extreme res without compression and 16x anisotropic filtering, he’d already be doing that!

In order to understand the vanishing point in Plane-Maker, we first have to look at field of view and the process by which X-Plane simulates a 3-d world on a 2-d monitor.

Field of View

Field of View is the angle that you get if you go from the left edge of your vision to your eye, then back up the right edge. In the case of a monitor, we can calculate this (depending on how far back I am sitting). For example, my 19″ LCD is 14.8 inches across the top; to have a 45 degree FOV I need to sit about 17.8 inches away from the monitor.

X-Plane lets you set the field of view. Imagine that you were sitting in front of a window on an airplane. As you put your face closer to the window, you can see more of the world outside. Effectively you are increasing your field of view. X-Plane works the same way – turning up the field of view parameter will increase the amount of “stuff” you can see.

Where Is The Horizon?

So where is the horizon? The answer is: it depends. Assuming you are looking straight forward, the most logical place to put the horizon is exactly half-way up the monitor. And this is what X-Plane does in any external view.

As you rotate your head up and down, the center of your vision changes relative to the horizon. But if you simply move your head up and down, the horizon doesn’t move. This is due to parallax. The closer an object is, the more it moves as you move your head. This is what lets me look “over” the dashboard of the car by sitting on a phone book: as my head goes higher, the dash board (close) appears a lot lower but the road (far) appears only a little bit lower. The horizon (very, very far away) doesn’t move at all.

This effect works in X-Plane. Try moving the view point up and down in a plane with a full 3-d cockpit, like the Cessna 172. As you move your head up and down, your ability to see the runway out the window will change.

2-D Panels

Things get weirder when we have a 2-d panel. A 2-d panel is sort of a flat image of what a 3-d cockpit might look like. We need some kind of correlation between the 2-d world and 3-d world…that is, where does the horizon appear through this 2-d panel. That location is the “vanishing point” in Plane-Maker.

Here’s where things get strange: what do we do when we scroll the panel? Do we move our head or tilt our head? The answer is: neither. Scrolling the 2-d panel simply scrolls the “window” within the 3-d world that we look through. This has the effect of moving the horizon (by the exact number of pixels the panel scrolled) without rotating your view point.

This isn’t necessarily the best way to scroll the panel, but it looks pretty good, and anything we do with 2-d panels is going to be an approximation.

And Now The Bug

Of course, there must be a bug in here somewhere…these blog posts are usually the result of an investigation into an edge-case in the sim. In X-Plane 930b6, we pick a vanishing point based on the 2-d panel when we are in 3-d cockpit mode.

Why would we do such a silly thing? Originally it was to keep the horizon from jumping when there is no 3-d cockpit object. This behavior is okay in that case, but here’s how we get burned: if the 2-d cockpit has to scroll, the vanishing point might be off the top of the screen. Authors who have made very large 2-d panels and separate 3-d cockpits see this as the 3-d viewpoint being stuck straight down. What’s happening is the vanishing point (and thus the center for the mouse) are off the top of the screen.

For beta 7 I am fixing this:

- If there is a 3-d cockpit object, the vanishing point will be the center of the screen, which is almost certainly the right thing to do for a real fully 3-d view.

- If there is no 3-d cockpit object (but instead X-Plane’s default of the 2-d panel floating in space) the vanishing point will match the 2-d view, but taking the default scroll position into account. This should keep the horizon at a reasonably sane point.

As a final note, it is possible to specify a 3-d panel without a 3-d cockpit object in X-Plane. Don’t make a plane like this. It’s a silly thing to do!

The code that decides what parts of the plane get drawn in what views is, to put it midly, byzantine. The code evolved, and in this process became more complex and convoluted.

One of the side effects was a series of bugs that couldn’t easily be fixed – typically it was a case where some new piece of code had to do some drawing, but the decisions on how to draw were being made by legacy code that had no business making those decisions.

So for beta 6 I rewrote that code.

Here’s what this means: if your airplane starts showing the wrong “stuff” in various views in beta 6, please send me the plane, and a description of what it does in 922 and 930b6.

The risk is that I may have missed some of the quirkier behaviors that 922 was capable of. My goal is to have 922’s behavior, but with clean code. So if things changed, please let me know!

Let me just clarify one thing about yesterday’s post on materials: the new material system will let authors edit material parameters like shininess; it will not let the user change textures.

Objects will continue to require texture atlasing (that is, the use of one texture set with the individual images combined). Inside the company, we call this the “crayon rule” – Austin’s original analogy to explain atlasing to our art team was that you draw slower if you spend all your time putting a crayon back in the box and taking a new one out.

So materials will let you change some macro-parameters of how the object is drawn, but not swap out the texture.

First, we’re not going to get an OBJ materials model in 930. 930 is crammed full of stuff, and I don’t want to add anything more! I am not sure when we’ll get OBJ materials, or even if this is how it will go down. But this is what I am thinking:

- Materials will be controlled on the “batch” level, that is, by using ATTRibutes. You’ll be able to change materials mid-object.

- Materials will be grouped into “material classes” – the material class will be mutually exclusive. So if we have a metal material class and a “plastic” material class, you won’t be able to combine them.

- There will be some kind of material class that corresponds to the current behavior, and all of the existing attributes will keep working; probably there will be a newer, cleaner way to state in an OBJ what you can already do now.

- You will set all material class parameters at once. This simplifies the syntax and assures that we don’t have any strange mix & match combinations.

To this last point, consider that OBJ currently has a number of strange cases where you can set attributes that don’t have any effect. For example, you can set the shininess while drawing the cockpit texture (which is unlit). Code like this has historically been buggy, partly because it’s not necessarily obvious to a human reader what the object should do.

I do not yet know how normal and gloss maps fit in. Normal maps may be useful to multiple material classes; gloss maps are somewhat material class specific (in that if a material class has no concept of gloss, the gloss map is moot). It is definitely advantageous to pack a normal map and gloss map into a single texture (a la blender).

The main point of material classes is to create the infrastructure for complex extensions to the material system in a clean way. Adding additional attributes creates an NxN problem – for each new attribute I add, I have to consider how it interacts with every other attribute. By comparison, a new material class by definition shuts all other material classes off.

X-Plane 930 beta 4 will be out real soon, and it has a somewhat significant new instrument feature: all instruments (not just generic instruments) can have additive lighting.

But wait – what is additive lighting? Additive lighting is the basic equation X-Plane uses for “lit” stuff. Basically it says that the _LIT texture is added to the daytime texture to simulate the effect of an object that reflects sun light and emits its own light. Here’s a

more detailed description.

It used to be that the _LIT textures for instrument overlays were used instead of the daytime ones at night. Generic instruments introduced a new lighting mode, “back-lit”, where the LIT texture is added to the daytime texture. This lets you make an instrument that has a light behind it to illuminate the markings at night.

In particular, when an instrument is back-lit, the amount of LIT texture added in is a function of the instrument light levels (the pilot can turn this up and down) while the amount of day time texture is a function of the sun and spot light shining on the area.

Originally I did not want to extend the legacy instruments to support back-lit lighting. What finally made me change my mind was the amount of detail in some of the standard mechanical instruments. As an exercise, I converted the six pack and nav instruments of Max’s default Cessna to generic instruments.

The conversion required a lot of new (and very weird) datarefs, some esoteric extensions to the generic needle instrument, and it lacked some of the finesse of Austin’s built-in instruments. All of these problems stem from one limitation: the animation action of generic instruments cannot be nested.

(Of course there is a practical consideration too – for an author with legacy instruments, rebuilding with generics takes time. Typically it took about 4-6 generics to model each built-in instrument in the six pack. The conversion only took me about eight hours, but I have access to the source code of the built-in instruments, a luxury authors would not be able to leverage.)

So in the long term, I am at least investigating the notion of nested animations and movements for generic instruments; I think that this would be the final flexibility needed to model just about anything with generic instruments.

But for the short term, you can back-light your built-in instruments; just set the lighting mode to “additive” and create the LIT textures.

A number of users have commented that the X-Plane 930 betas looks “shinier” than before. There are actually two separate features going on :

- Separate specular hilights. Specular hilights are bright areas on the plane that simualte the refelction of the sun on a shiny surface. X-Plane has had specular hilights for a while (available by the “shiny” check-box in Plane-Maker or ATTR_shiny_rat for an OBJ). What’s new is: while previously the hilights were modulated by a texture, they are now independent of the texture. This change means that even a black surface can look shiny now. Before the black surface would “tint” the hilight black, making it invisible. Now we can have a white hilight on a black surface for a glossy look.

- Per-pixel lighting (when shaders are on). Before the lighting calculations were performed on each vertex on a model, then the color from the lighting was interpolated. The problem with this is that if there is a very local lighting effect (like a specular hilight) that is smaller than one triangle, you can’t see it (since we can only see the lighting at far apart vertices). With 930, the lighting calculations are done per pixel, making the lighting effects look smoother.

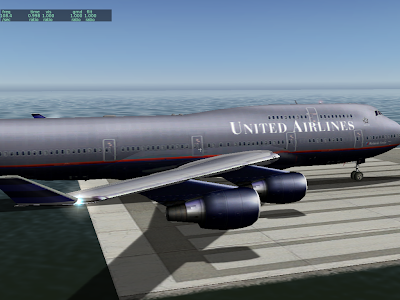

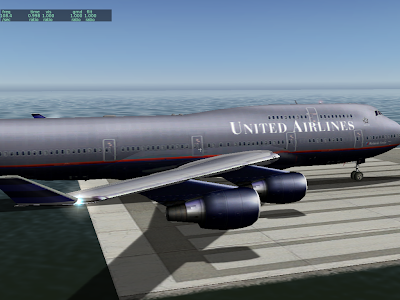

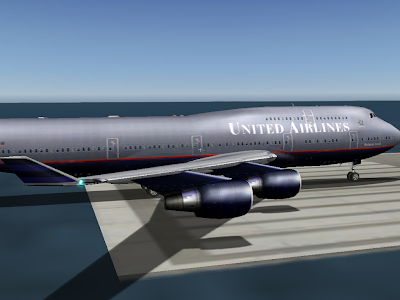

Here we have the default 747, as of 922. It’s a little bit tricky to tell what’s going on because the texture has been painted to look like there are lighting effects. But the white “specular hilights” on the engine nacelles are due to the sun position. Lighting is per-vertex and specular hilights are not separate.

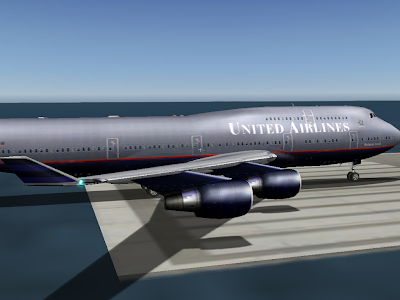

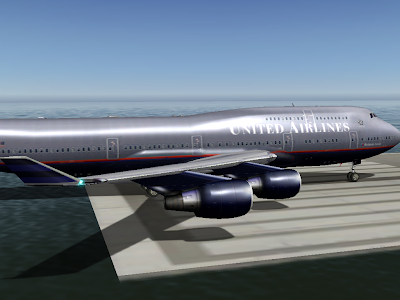

Next we have the same plane in 930 without shaders:

Note the increased brightness on the nacelles and fuselage. What’s happening is the hilights are no longer modulated by the texture, so they show up a bit more.

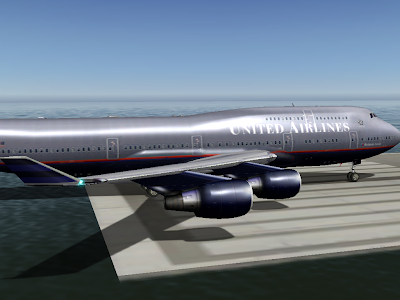

Finally, the plane in 930 with shaders. Now the hilights look smoother and much brighter. This is because the hilights are calculated on a per-pixel basis. Note how the hilights are small – smaller than the triangle size on the engines. We didn’t get the full “glare” effect before because the brightest part of the hilight did not land on a vertex at all, and was thus never seen.

Note that the change in specular hilight handling (moving to separate specular hilights) is a bit of a compatibility break. Previously authors could count on not having specular hilights on dark parts of a plane, even if they set the plane to be shiny.

I am not sure how we will ship the final version of 930. I have received very few (none, to be exact) complaints about dark surfaces appearing “too shiny”, and a lot of users like the new shiny look.

The alternative to the current scheme (specular hilights are separate by default) is to have this be a selectable feature. Older planes would look the same as they always did, but planes would have to be modified to make them look truly shiny.

ATTR_hard is the OBJ attribute that makes the geometry of an object mesh interact with X-Plane’s physics engine. ATTR_hard object has a long history of weird behavior, and its behavior in X-Plane 930 is no exception.

The History

- Before X-Plane 815, hard surfaces acted horizontal regardless of the actual OBJ geometry.

- From X-Plane 815-922, sloped hard surfaces work as expected, but vertical hard surfaces do not work. Animation is ignored for hard surfaces.

- Starting with X-Plane 930, animation commands affect hard surfaces. However, vertical surfaces still do not work, and an animated surface does not create friction under the plane.

(In other words, if you put the plane on a platform and move the platform horizontally, the plane will be pulled with the platform due to friction between the platform and the wheels.)

In all of these cases, what we have is a limited implementation that doesn’t correctly capture all expected behaviors. Why don’t we have a better implementation? There are two factors.

- In some cases a more correct implementation might take significantly more CPU power. It is important that we not raise the CPU requirements of X-Plane mid-version run.

- In some cases, we simply don’t have a better implementation coded yet. Remember that X-Plane is primarily a flight simulator. My pilot friends tell me that it is bad form to collide the airplane with anything during flight. So the goal of OBJ collisions is more to detect poor flying than to correctly model the resulting aftermath. X-Plane is not GTA4!

What Do You Do With a Buggy Feature?

Very simple: don’t use it if you can avoid it! I don’t mean “don’t use ATTR_hard” – it has legitimate uses. Rather I mean: don’t depend on the buggy behavior as a feature.

For example, before 930, animation would affect the drawn but not physical OBJ. I would say that given that bug, the only safe thing to do is to not animate hard objects. Animating hard objects to take advantage of the schism between drawing and physics would be assuming that the bug will stay buggy forever.

What Can You Do Now?

In X-Plane 930 hard object animation is a lot better than it used to be, but still not quite correct. The remaining limitations are:

- There is no friction. If you move a platform horizontally, the plane is not dragged along. So you can’t really build horizontal elevators. (You can build a platform that moves vertically and move the plane around that way.)

- There is still not support for vertical hard surfaces. Like before, to make a solid “wall”, make the wall thick and make the top of the wall hard. But bear in mind that the collision detection in this case is catastrophic; your plane will be heavily damaged by even minor contact with the wall. X-Plane doesn’t support horizontal collisions right now.

- Hard surfaces are ignored for vehicles. If you are replacing the car set, don’t add hard surfaces – it might turn out that some future implementation does look at them – if that happened, how would you know what the CPU hit is?

Even given this limitation, you can now make a building with limited access controlled by animation; using a “deck” for the roof and a hard surface for the tops of the walls and the doors (which are animated) you can control access.

I have been trying to put documentation on the X-Plane Wiki, and use this blog for announcements and “the inside story”, rather than letting the blog turn into a poor-man’s users manual. An aircraft developer asked me via email whether there was a blog entry on some of the pitfalls of the v9 panel lighting system. There is not, and the lighting system is under-documented. I will be working on improving the documents over the next few weeks, but the point of this blog entry is: “how did we get here?”

I am a huge fan of incremental software improvement. That’s the subject of another blog post (perhaps on another blog), but for now I’ll say this: all changes to the rendering engine since version 8.0 have been incremental ones, and yet if you were to look at the code, you wouldn’t see a series of band-aids taped on top of each other. Each incremental change leaves the rendering code “fully updated”, as if it had been written yesterday. I start each new scenery feature by first reshaping the existing code into the most useful form for what we want to have in the future, and then coding the new feature is relatively simple.

But this strategy has an Achilles heal; if the code being refactored has a public interface (whether it is a file format or programming API), then all of the intermediate steps in the journey become requirements for future products in order to maintain backward compatibility.

This is not a problem as long as the programmer knows where he is going. The danger comes when one of the intermediate steps is actually a step in the wrong direction, and becomes dead weight around a future design.

A Reasonable Progression: OBJ

The OBJ 800 file format has had a reasonable progression* since its birth in version 8. It has gained a number of new features, but each one has generalized and made more powerful previous ideas, such that “legacy behaviors” are not so painful. Some examples:

- Hard surfaces may now be decks (e.g. you can fly under them) or not, and you can specify what kind of hard surface you have. The original hard surface command was simply “it’s hard” or “it’s not”. But viewed under the lense of the new scenery system, that old hard surface command implicitly implied “the surface is smooth” and “the hard surface is not a deck”. So the new hard surface command is a more general version of the old one, which continues to work under the new system.

- Animations in version 9 can be key framed; in version 8 you simply specify start and end values. But start and end values are just like having two key frames. So viewed under the lense of the new scenery system, all animations are key framed; older objects always just have two key frames. The new key framed commands are a more powerful, more general version of the old ones.

I can’t say that the relatively pain-free evolution of OBJ files over the last 4 years comes from good design or genius on my part – in truth it’s probably just good luck. But I think one thing has helped me keep the new OBJ extensions relatively sane: most of them are conceived several months before they make it into X-Plane.

I have a scenery system to-do list that will last me at least another four years; most of it is filled with things that Sergio has asked for. This to-do list acts as sort of a road map for future scenery system extensions; for any possible OBJ change, I can look at it relative to the other todo items and ask: “is this extension going to play nicely with things to come?”

(As a side note, this is one of the reasons why there are not light maps in any of the X-Plane modeling formats. Light maps don’t play well with a number of other scenery system extensions. I want to resolve the conflict between these future additions before they go into the sim.)

Wandering In the Desert

By comparison, the evolution of the panel system in version 9 has been more like wandering in the desert than a straight line toward a goal. Repeatedly, I put features into the panel system without a clear roadmap of where we would end up or how they would work together. The result is what you see now when looking over the panel documents: complexity and chaos.

Basically there are several major changes to the panel system that affect each other in strange ways:

- A more complex lighting model on the 2-d panel in version 920. (That is, the 3 2-d spot lights, and generic instruments with back-lit, mechanical, or glass lighting.)

- A more complex lighting model in the 3-d cockpit in version 930. (That is, 3-d spot lights, ATTR_cocpkit_region and generic instruments with back-lit, mechanical, or glass lighting.)

- A separate panel used only to provide texture to the 3-d cockpit. (That is, the 3-d panel.)

The problem is the order that they were invented: first ATTR_cockpit_region, then the 3-d cockpit, then back-lit generic instruments, then 2-d spot lights, and then 3-d spot lights.

The result is two sources of confusion:

- Some combinations of features simply don’t work together. Since all of the features appear to be independent, I sometimes get bug reports on these. For example, you can’t use the 2-d spot lights on the 3-d panel. This is not a bug, it is by design! I will explain why some of these limits exist in future blog posts.

- Among the remaining combinations that do work together, there are a lot of choices about how to structure a plane – too many choices!

This second point is a tricky one: X-Plane has to continue to support whatever set of features was available for any given release (864, 900, 920, 930) so that older planes continue to work. But some of those combinations (e.g. the ones that exist in version 900) don’t make a lot of sense for new planes made in 930.

I am open to ideas on how to solve this. I intend to document a “correct formula” for a modern plane, perhaps with tutorials, on the Wiki. I am also considering programming Plane-Maker to flag unusual combinations of features as a warning when saving 930 planes.

Either way, I fear I’ve learned my lesson from the panel system: incremental improvement of code is only a good idea if the programmer knows where he is going! Next time I will use Google Maps. 🙂

* I suppose that whether you think the OBJ 800’s evolution has been reasonable depends on your standards for file formats. OBJ 800 absolutely does show growing pains. I would only say: consider the number of revisions and the change in the hardware platform OBJ 800 feeds when you consider its stretch marks.